Consumption is not going to go away, but how can products and services be designed such that they use fewer precious natural resources and materials? Designers and the entire design chain have a key role to play in fostering the circular economy.

Consumers’ attitudes towards goods and ownership are changing radically. The planet is warming, and consumers increasingly want sustainability in the goods and services they buy. They also expect responsible actions from the companies who provide these items. Ideas of ownership are morphing – many of the old ways are being eroded. Not everything has to be owned permanently or bought new, but novel means of acquiring and using goods are spreading.

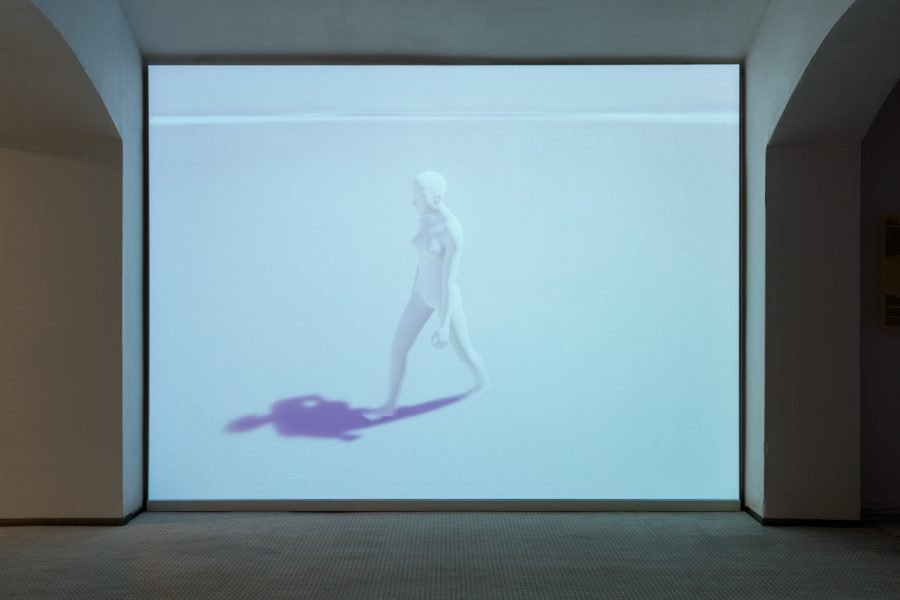

Much depends on the designers and the design branch if consumers are to be able to find more sustainable ways to live. In December 2022, a panel webinar hosted by the Design Museum in Helsinki explored the changing relationship between design and materials under the headline of Design in the (Non)Material World.

Oskar Korkman, a Finnish market strategist and the co-founder of Alice Labs Partners, is one of the researchers behind a recent international project – Stuff in Flux 2 – that examined changes in consumer attitudes and behaviour across the world. The survey’s findings were collected in a report entitled The Stuff People Want.

Korkman observes that consumers are now interested in products that do not leave them with a sense of guilt about their purchase. Before long, key consumer expectations will be for longevity, usefulness, and guilt-free joy. As he sees it, the core of the problem lies not in the consumers but in the products. He argues that manufacturers are prone to using the old excuse that consumers are “not willing to pay for” sustainable, responsible solutions or environmentally friendly products.

Information has an important role to play in the success of reducing how much we consume, adds Korkman. For some consumers, responsibility is bound up with the durability or longevity of a product, for others it is in the ability to re-use or repurpose the item. Korkman stresses the need for sensitivity in the messaging. There is nothing to be gained by selling a product to young people with the message that they are getting something less than before. People will always consume, he says, hence it is necessary to create the sort of things – “the stuff people want” – that generate more positive experiences while using less material: in essence, more value and more satisfaction from fewer products.

One of the big questions going forwards is just this: how to design experiences, as opposed to products?

The study produced by Korkman and Alice Labs Partners indicated that consumers’ attitudes towards ownership are also in flux. Consumers no longer feel the same tight bond with items in their possession: many perceive themselves instead not to be the end-point owner of something as much as its temporary custodian or steward, embracing ideas of “circularity” and “flow”.

The selling of used and refurbished products is no longer just a small-scale business. To take one example, the Finnish company Swappie has succeeded in scaling up the testing and repair of used smartphones to be sold through reliable online channels to customers across Europe.

According to Oskar Korkman, sustainable development really should be seen as a change in our way of acting and a new set of core values for these actions. And design has a pivotal role in this change process: it helps us to develop more sustainable and responsible products, but also to transform ways of thinking and behaving.

The traditions of usability and functionality typically associated with Finnish design are likely to be a great advantage in the markets of the future. Features like practicality and simplicity – and their role in aiding long-term usefulness – appeal to the so-called “leading edge” consumers targeted in the recent survey, and they are not seen to reduce the pleasure of using items, but to increase it.

İdil Gaziulusoy, Associate Professor of Sustainable Design in the School of Arts, Design and Architecture at Aalto University, sees that whilst we are still a long way from getting a grip on the climate crisis, young people are becoming more aware and enlightened. She takes heart that they are demonstrating ever-greater responsibility over the crisis. We already know what has to be done to reduce consumption, and Gaziulusoy calls for action and the will to get things moving.

What has to change, then, in order that consumption can be reduced in the design, architecture, and fashion branches?

Architecture student Matti Jänkälä from You Tell Me, a collective of students and young architects, feels that changes have to come in the training of architects. The tuition has to meet the demands of the day: without a paradigm shift in thinking it will not be possible to design and erect a better and more sustainable built environment.

In Jänkälä’s view, the construction industry is conservative and risk-averse. Since construction projects are generally huge and expensive, there is a tendency to play safe and to apply the brakes. Consequently, change in this sector is slower than in many other fields. Money is also a negative driver in the renovation of old buildings – it is easier and cheaper and more predictable to build new from scratch than it is to repair something that is already there. Repairing and renewing the old is more challenging; it requires more intimate knowledge of the building and greater precision – and it is expensive.

Susanna Björklund, Senior Lecturer and Foresight Specialist at LAB University of Applied Sciences, underlines the importance of critical thinking, in order to produce real reductions in consumption. Many of us inhabit bubbles that might make it feel as if things are moving fast and the world is changing, but in reality, the global picture is that the entire sustainability discourse is still in its infancy – it is not easy to turn a huge ship around.

Everything has its downsides, too. If, for instance, we see an end to the fast fashion business model in favour of something more sustainable, this will also mean massive numbers of jobs disappearing. How are we to address challenges like this?

“Going digital” and moving over to the Metaverse is not without its problems, either. Even if it ends the creation of new physical goods, there is no denying that vast quantities of energy and resources are used, for instance in the minting of NFTs. Equally, electric vehicles are currently heralded as a solution to the greenhouse gas emissions of road transport, although the production of the vehicles and their batteries uses colossal amounts of natural resources and leaves a huge carbon footprint.

According to Susanna Björklund, too much time and energy is today focused on resolving distinct present-day problems, when it should be more on a holistic footing, looking at connections and at changing the whole way in which we think and how we make things.

İdil Gaziulusoy shares this view. She argues that the biggest mistake in the struggle against climate change is one of short-sightedness, with policy focusing on “putting out fires” in the next 3–5 years, rather than looking further ahead to a “desirable, sustainable, post-carbon, and just world” that we may want – and then making decisions based on this objective.

As one concrete example, Gaziulusoy picks up the electric vehicles mentioned by Susanna Björklund. At present, the focus is on EVs and HEVs versus the old internal combustion engine, even if this is really only a stopgap solution to a much wider problem. The entire concept of individual car ownership is itself basically “unsustainable”: our longer-term goals should be to provide alternative means of mobility.

Björklund believes that fashion should concentrate more on products that stand the test of time, garments that the consumer loves and wears for ever. Longevity in this respect does not have to mean boring or unfashionable, and if the item is kept for a long time, it does not even matter that it is bought new rather than second-hand. The main thing is that the clothing lasts and is in use.

Matti Jänkälä stresses that future solutions will be found from cross-disciplinary cooperation: it is important to to be able to listen to others and to learn from the ways things are done in other branches.

Design has a very significant role to play in the building of a sustainable future. Nobody is going to buy an ugly, undesirable product just because it is sustainable, argues Björklund. What we need, besides the aesthetic solutions, are legislative measures and changes in taxation that support responsible choices, in order that sustainable solutions can really become a part of our future world.

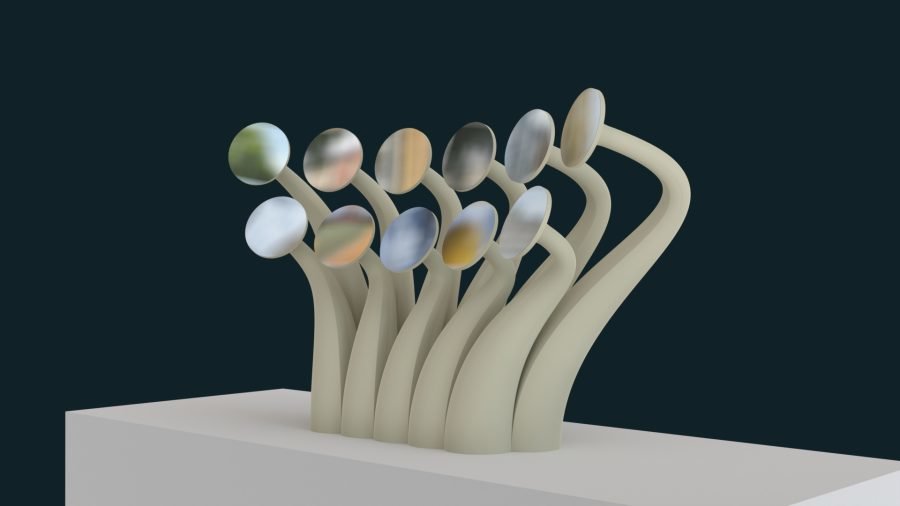

What if? Alternative futures at Design Museum 9.9.2022–12.3.2023

Photos Design Museum

Fashion Finland

Editor-in-chief Sami Sykkö | sami.sykko@fafi.fi

Head of Content Johanna Rämö | johanna.ramo@fafi.fi

Content Creator Rebekka Silvennoinen | rebekka.silvennoinen@fafi.fi