Design is at a turning point, on the cusp of momentous changes. One foot is still firmly planted in the industrial era, but the other is already striding towards the digital age, explains the award-winning designer-architect and digital visionary Kivi Sotamaa.

The world’s first digital fashion house is The Fabricant. Established in 2018, the company is the brainchild of Finnish native Kerry Murphy, carrying a vision of building an entirely new ecosystem: a digital fashion industry, creating “the wardrobe of the metaverse”.

The Fabricant promises to throw open the doors to anyone who wants to become an active creator: it believes that in the digital world, a young designer living in Dakar with access to IT tools will be on an equal footing with his or her peers in Paris. Designers around the world can collaborate and co-create on an online platform, The Fabricant Studio, and can share the financial rewards for their work.

In addition to avatar style – virtual clothing for the virtual world – The Fabricant makes digital mock-ups and samples: 3D images of new collections for commercial fashion brands. The brands can derive tangible benefits when using the digital images to sell the clothing to retailers or customers, improving sustainability and reducing the materials and delivery costs that would arise from producing physical samples and sending them to potential customers.

On the design front, the potential offered by digitalisation is equally boundless. Take the smartphone, for instance. It is a physical device familiar to us all. A design item, copies of which have been produced for the global market in their tens of millions. And yet it is a product that has negligible use or value without its digital interface element.

“In many products, digitalisation is an extension of the physical interface”, says designer Kivi Sotamaa. Sotamaa founded the Aalto University Digital Design Laboratory (ADDLab) in 2012, and he has forged an impressive international career as an architect. His work has been shown extensively, at MoMA in New York, at the Venice Art and Architecture Biennales, and at the Chicago Art Institute, as well as in countless design and architecture publications.

“Digitalisation in architecture is present these days across the entire value chain, or the production process. Design work can be carried out creatively using desktop software, and the digitally designed product can be manufactured by automated robots using AI. Small items, such as smartphones, can also be 3D printed, which has advantages when making prototypes.”

The award-winning pioneer of digital design is reluctant to make a distinction between design and architecture, even though there are naturally differences when considering industrial products, furniture, and buildings. Rather than design alone, Sotamaa uses terms like development and formulation.

During the industrial era, Kaj Franck (1911–1989) designed an iconic series of strikingly simple drinking glasses that were stackable and were also ideally suited to large-scale mass production. Decades later, digitalisation provides us with an economically viable means of returning to the handcraft traditions of a time before Franck, where products were marked by unique surface ornamentation and by small production runs. Today’s robots are faster and more precise than the craftsmen of yesteryear, and they do not count the hours they work.

We are currently in the throes of a paradigm shift, argues Sotamaa. One foot is still firmly planted in the industrial era, but the other is already striding towards the digital age.

“When you recognise the potential of technology, the sky is the limit. In the digital world, the importance of innovative ideas becomes even greater, for modern manufacturing technology can be harnessed to serve any design solution under the sun.”

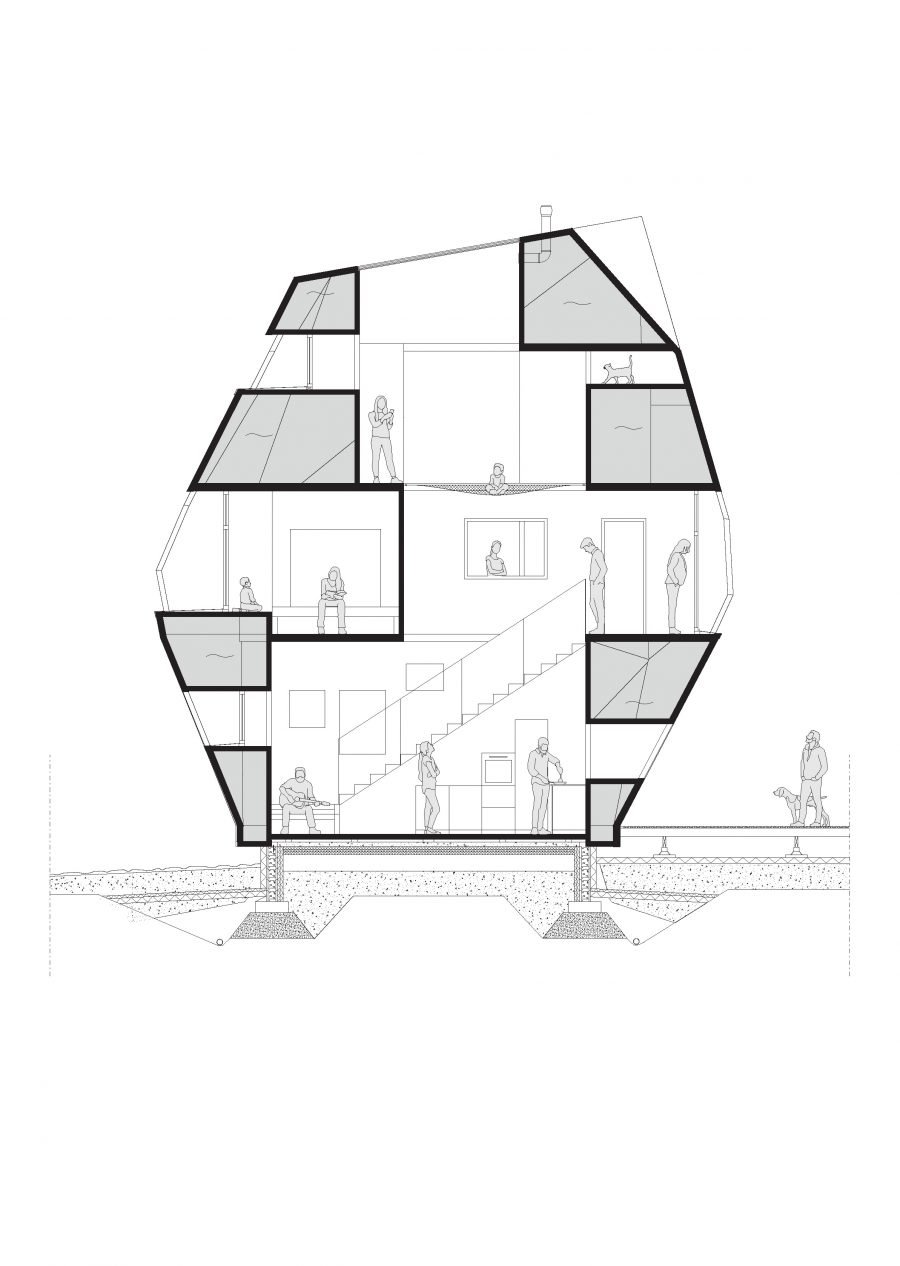

One example of the new vistas opened up by digitalisation might be architectonic breakthroughs like Meteorite, a polyhedron-shaped residential building in Eastern Finland. Meteorite, conceived in 2019 by Sotamaa in partnership with his sister Tuuli Sotamaa, is a completely digitally designed home of cross laminated timber construction, in which all the modular wooden elements have been prefabricated and cut using industrial robots.

“In both the economic and the technical sense, the house could be realised relatively easily, using methods that until very recently were completely off the table. The idea behind Meteorite was also to show how diverse the built landscape could be, if architects were able to exercise greater freedom”, notes Sotamaa.

Designers of digital services and user interfaces must be able to deliver applications that are effortless to use, offering smooth and intuitive navigation.

“The design of virtual environments is its own realm, but a realm where one can apply much of the experience gained from developing physical environments. It is as if we are creating a digital twin for our analogue world”, Sotamaa explains.

The analogue and the digital worlds meet in new kinds of applications. One such is Woebot, an American-made artificial intelligence powered chatbot created by medical professionals. Woebot offers digital therapeutic solutions, helping users to monitor their moods and to manage their mental health when needed. A slightly similar concept is the digitally created virtual influencer Myrsky (“Storm”) generated by MIELI Mental Health Finland. Myrsky’s role is to serve as a kind of virtual barometer of all the feelings, emotions, and mental health difficulties experienced by young Finns, particularly in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

Interaction is also needed in digital environments. Traditionally, one of the yardsticks for successful design has been to measure how well the human and the environment can interact in the chosen space.

The potential to be tapped in digital design does not come without some questions. How, for instance, are we to determine and agree the immaterial rights when the object is, say, a table lamp whose design is based on the idea that each individual lamp is customised, with subtle, barely perceptible differences? As the fundamental principles underpinning design are changing, so the legislation will have to keep pace.

“In practice, digitalisation is already among us – it is everywhere. New ideas are surfacing all the time, and it is impossible to gauge their commercial potential without experimenting and making prototypes”, Sotamaa adds.

“Then again, digitalisation as such is not automatically always the right way to go. It makes no sense to erect the precast concrete buildings of the 1950s using industrial robots, and similarly there is no point in trying to assemble the results of freeform digital design using simple machine tools intended for mass production. The designer should go through all the links in the value chain and be able to recognise a need – and then join forces with other professionals to create something entirely new.”

Photos Tuukka Koski

Fashion Finland

Editor-in-chief Sami Sykkö | sami.sykko@fafi.fi

Head of Content Johanna Rämö | johanna.ramo@fafi.fi

Content Creator Rebekka Silvennoinen | rebekka.silvennoinen@fafi.fi