As waste turns into a resource, new opportunities are born. Three designers share their take on consumption and ways of solving the waste dilemma.

Designers have a problem. A problem of waste. While previous generations may have dreamt of designing new products in a seemingly endless flow, the designers of today no longer have this opportunity. They have come to understand the problem less as a lack of products but rather as an excess of everything.

The challenge for the Western consumer has long since surpassed the satisfaction of basic needs. Overconsumption is already threatening the future of the whole planet. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature WWF, we would need three and a half earths – instead of just one – for all nations to consume as much as the Finns. This year, the ecological footprint of Finnish people surpassed Earth’s biocapacity already early in the year, more precisely on 31 March. Since this date, we have been living in debt.

What follows overconsumption? An immense pile of waste at the very least. The image is far from graceful, but what if we called it a resource instead? A wasted resource. Would this reformulation change our relationship with waste and with consumption?

How do we turn an old thing into something new, make something useful out of needlessness, create value where there is none? How can waste be redefined and released back into circulation? What kind of opportunity might the trash dilemma pose for the designer?

These are some of the questions that fashion designer Tuomas Merikoski, architect Ella Müller, and designer Irene Purasachit have been considering. They all have an interest in materials and designing them, but all are also curious about waste.

Why are we such bad consumers?

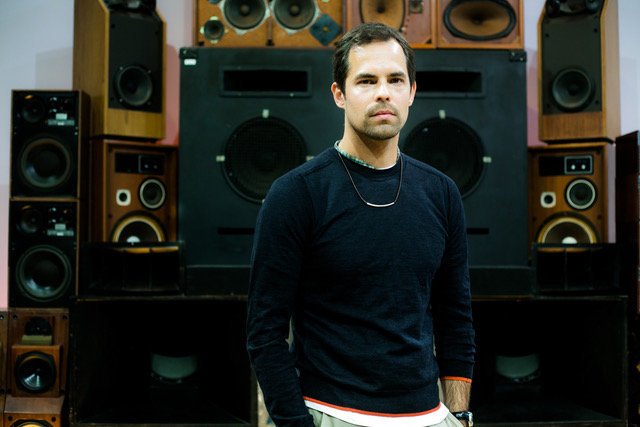

Fashion designer Tuomas Merikoski, Paris

“I am not a middle-of-the-road consumer, and I enjoy all kinds of things that are different. I ended up working in fashion because it combines artistic expression, practicality, and the satisfaction of various needs.

In my line of work, I see what consumption is. I’ve been a stranger to fast fashion for a long time: mass consumption, low prices, and the lack of respect for clothing items and design terrify me. There are some 150 billion pieces of clothing manufactured globally every year, and every single second a big truckload of clothes ends up in the trash. The fashion industry is one of the biggest polluters in the world. We still relate to clothing in a very naive way.

There is a huge amount of used clothing out in the market. As an example, two of the biggest wholesale storages are in France, with millions of clothing items. The greatest challenges in reusing lie in half-baked recycling and the trickiness of sewing clothes again.

I launched the Recoded line that will be out in early 2023. Its basic principle is to make fashion that is just as exquisite as before, but from 100% used and recycled materials. The innovation is the industrial manufacturing process, meaning that production is based on large batches instead of one-off pieces. Our clothes are available in various sizes, and the products correspond with new items in price and availability. Furthermore, every item is tagged with an individual number and QR code, which link to information about the clothing item and its manufacturing process.

The change towards more sustainable consumption can only happen if it is easy for the consumer to choose a better alternative over a worse one. The end result of the new clothing item still needs to satisfy the designer’s creativity and the needs of the paying customer. Desirability can’t only be based on responsibility, and a product must also succeed through other parameters, perhaps even better than an irresponsibly produced item.

We designers have an important role in the process, because we are the ones who create the product. We can make propositions and shift the design process toward greater responsibility. Success is always based on the collaboration of the creative designer and the business manager, also in questions of responsibility.

I intend to proactively change my own way of working, and nowadays I see my designs in a different light. A new way of designing is to reuse old materials directly. This changes the design process, the fine-tuning, touch and feel, and final treatment. The feel of vintage is very rich, and it is hard to copy. It creates a whole new dimension for creative work.”

Fixing is the future

Architect Ella Müller, Helsinki

“I’m more interested in old houses than new ones. Demolishing them for new construction seems wasteful and frustrating.

Construction is linked to all environmental problems from climate change to the diminishing of biodiversity. It causes emissions and consumes an immense amount of virgin natural resources. I wonder if we could limit the harm caused by endless renewals with the use of political instruments for instance, or will it only end when natural resources run out?

I finished my architecture studies last spring. For my thesis, I considered the cultural dimension of construction waste, and how buildings and urban environments are classified as waste. It is hard to say when a building becomes waste. Does it happen in the moment of demolition, or already before it? Is it in the moment when a new building is granted a fifty-year lifecycle for instance?”

”We often look to engineering sciences for solutions to the environmental impacts of construction. In my master’s thesis, I link the problem of construction waste to a wider societal discussion. I consider construction waste from the viewpoint of values and aims, and look for the roots of ideals of renewal and newness in the history of modern architecture. I want to question the predominant culture of construction.

It may be difficult to stand up for the modern building stock with arguments of heritage protection, because the stock is not yet old enough. Renovating more ordinary buildings would also be more ecologically sustainable than demolishing them. Renovation often comes down to money and will. Office buildings from the 1970s have been built atop of pillars, for instance. There should be no obstacle to maintaining them, because it is easy to alter the spatial planning.

I believe that the future of buildings lies in renovation. This can already be seen in architecture studies, and students are seeking out new ways of operating. It is interesting to see what kinds of ways will be developed for maintaining and utilising modern building stock, from restoration to circular economy practices for building components.

I also wish that residents and other building users would give more value to existing characteristics and stylistic features that are not currently in vogue.”

Waste can be designed

Designer Irene Purasachit, Berlin

“I took an interest in design already in school when I realised that everything around me had been designed by someone. I come from Thailand where there is a huge manufacturing industry, the impact of which can be seen everywhere. During my product design studies, I understood that as a designer I am also promoting consumption. I started to think about what I could do about this.

I first became curious about natural materials, and then innovative biomaterials. I started a project with an aim to produce material out of food waste. In order to succeed, I needed scientific knowledge and I looked for a study programme where I could operate between science and design. I found the Aalto University Chemarts programme and moved to Finland.

I’m interested in flowers and wanted to be a florist at some point. When I visited a Thai flower market, I saw how much flower waste was produced when the surplus flowers were thrown out along with their plastic wrappings. I thought this should change, and I started to develop fibre out of the stems and leaves of waste flowers, as well as colour pigment from their petals. An innovative, non-woven material resembling leather was born: Flaux.

I have now finished my first products made of Flaux. They are still prototypes but they clearly show the potential of the material. It needs to be made even more sustainable and easier to use, but it will then become possible to transform a bigger amount of flower waste into new material.”

”Last year, I was chosen as the winner of the New European Bauhaus – Rising Star competition organised by the European Commission. It was amazing to receive recognition for my work, especially since I am not European. I used the cash prize to continue my development work together with my business partner Chanawan Danpan. We live in Berlin nowadays, as we were given the Berlin Newcomer StartUp Award for our Flower Matter initiative.

When you design something – be it a product or a process – you are inevitably using resources. It is the designer’s responsibility to examine the product from a wider angle, and not merely produce more for the sake of production. We need to know why a product is designed, what its aims are, and whether it is necessary.

Waste can be a resource. On the other hand, waste is waste. I feel it’s primarily smarter to control how much waste is created. It is much more efficient than trying to come up with new purposes at the end of the lifecycle, which is what I do. But when waste can’t be completely erased, we need to consider if we can turn it into a resource.”

Photos Irene Purasachit and Marcelo Deguchi

Text Anna Varakas

Translation Simo Vassinen